It is now extremely well-established scientifically that COVID-19 spreads in shared air — across distances greater than six feet in enclosed spaces. But public recognition of this fact still lags, probably because of messaging that counterproductively suggested the main risk lies in shared surfaces and short-range transmission.

The latest Hawaiʻi Department of Health cluster report, published on October 28, 2021, continues the reports’ laudable trend of attempting to correct this public misunderstanding. The October 28 report centered on a cluster of “30 COVID-19 cases associated with an elementary school on Oʻahu.”

In its investigation, DOH found that the school did take multiple steps to mitigate risk, including “mask wearing, physical distancing, and student, faculty, and staff screening and testing on campus.” One thing the school did not do? Ensure proper classroom ventilation. “Teachers were reported to be keeping windows and doors closed to limit outdoor noise levels, and to maintain the central air conditioning,” according to the report.

In response, “DOH provided the school with options and guidance that would improve classroom ventilation,” according to the report. “Implementing techniques to improve airflow in classrooms, in addition to the core essential strategies, adds an extra layer of protection to prevent the spread of COVID-19 between students.”

This is not a surprise

Earlier this year, the New York Times published a story about this exact scenario, with the headline “Why Opening Windows Is a Key to Reopening Schools.”

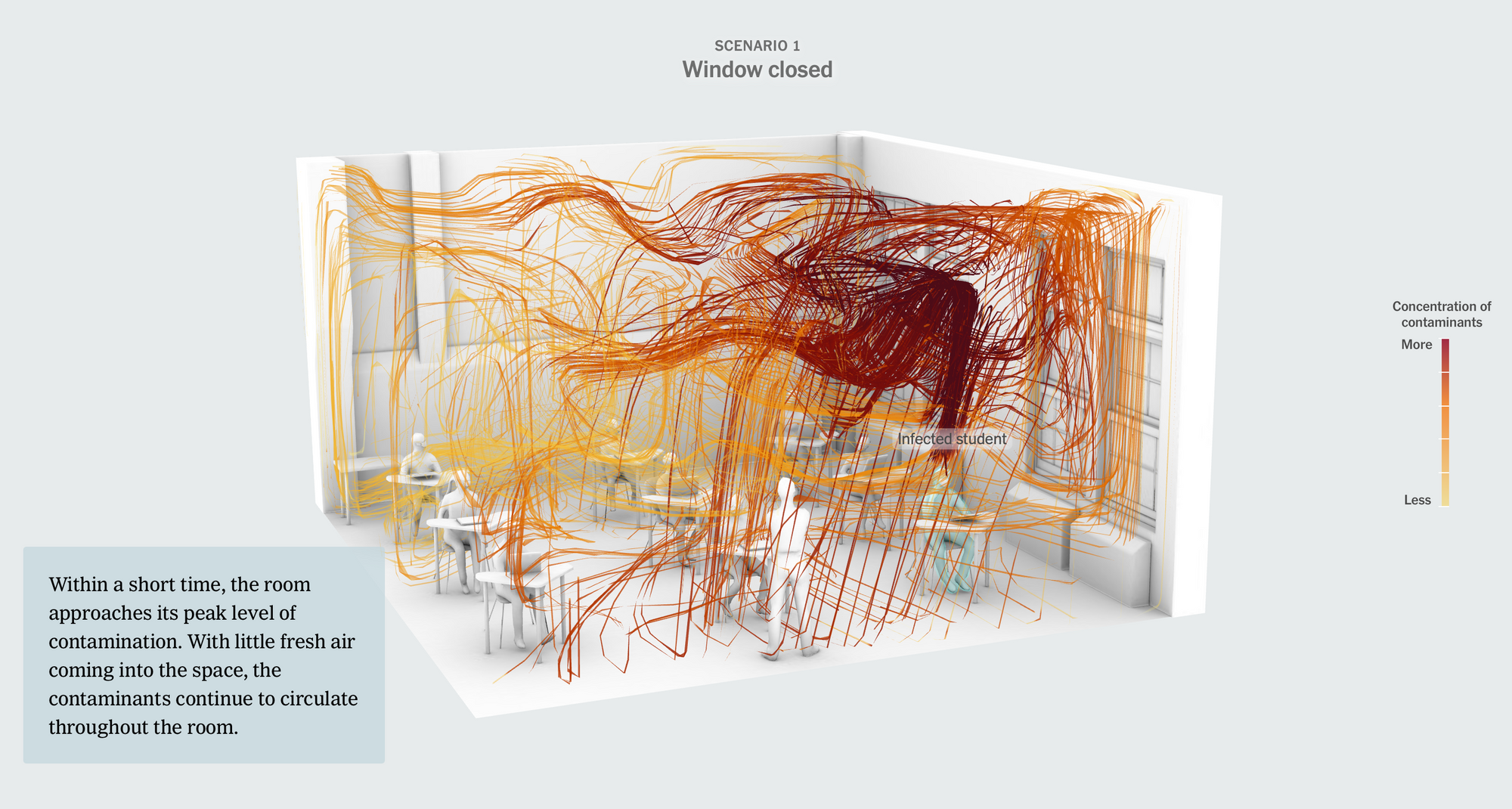

The article simulated what would happen in a classroom with just nine students, all sitting six feet apart, wearing cloth masks, similar to the Oʻahu school described in the DOH report. Yet “[w]ith all of the windows closed, the room would lack sufficient ventilation. That’s a problem with an airborne virus,” the article points out.

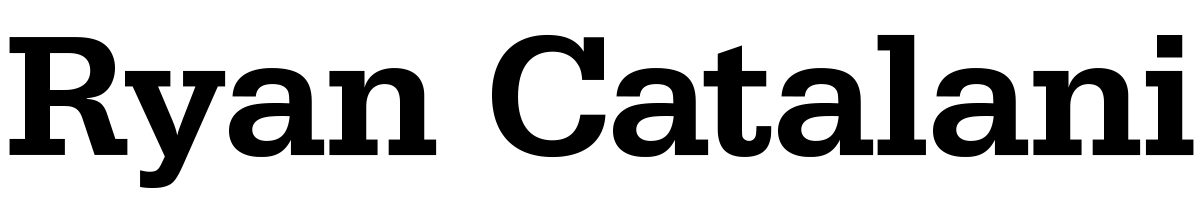

In this shared-air classroom environment, where about “3 percent of the air each person in this room breathes was exhaled by other people,” an infected student’s virus-laden particles quickly envelop the room — even reaching students more than six feet away.

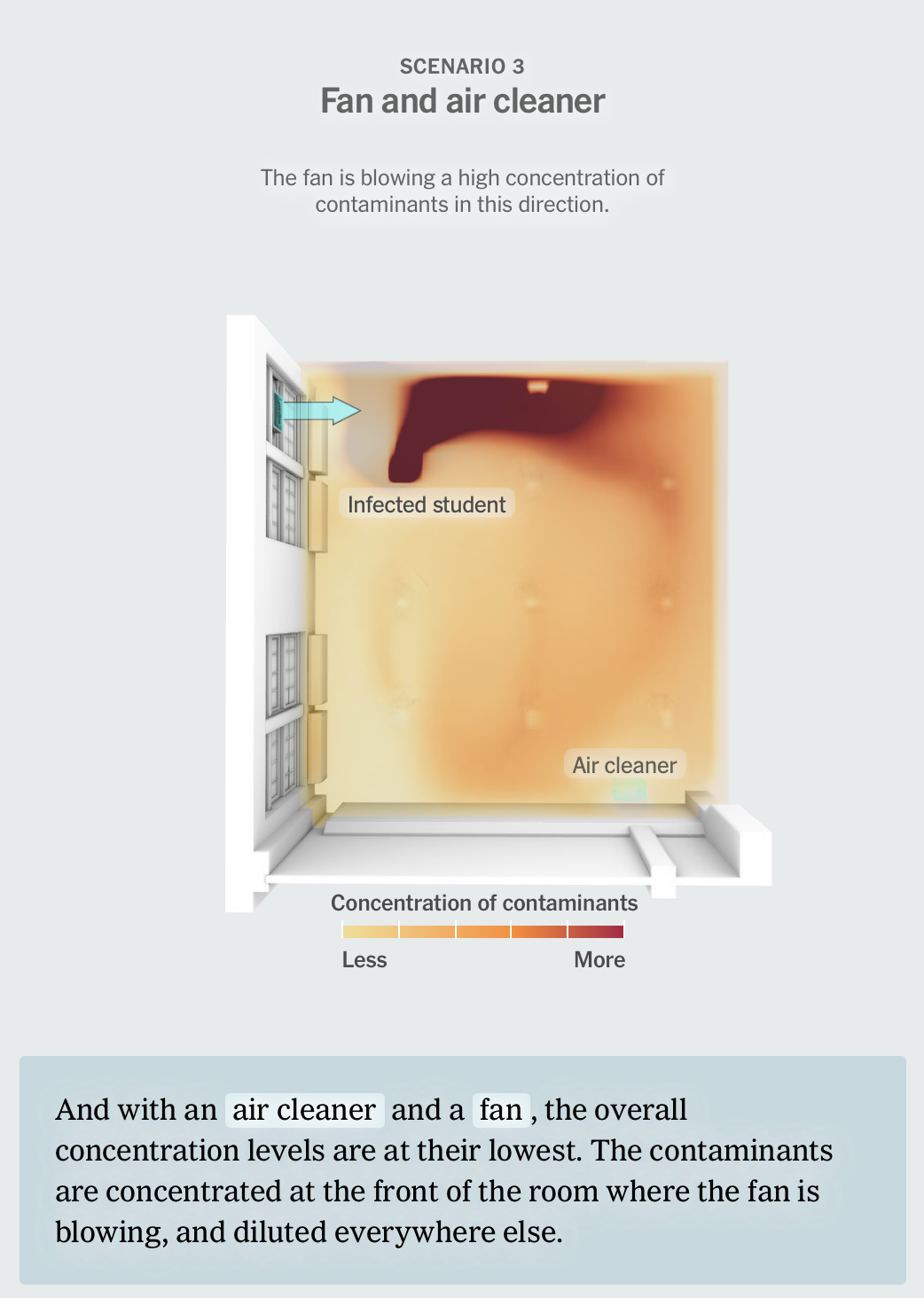

Just opening one window makes a huge difference in the article’s simulation, getting the classroom to four air exchanges per hour. Adding a fan and air cleaner with a HEPA filter gets the classroom to six air exchanges per hour. (“The Healthy Buildings program recommends four to six air exchanges per hour in classrooms, through any combination of ventilation and filtration,” according to the article.)

“It has been shown that the virus remains viable in suspended particles indoors for more than an hour,” said University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Timothy Bertram. “In rooms with good ventilation and/or in-room filtration, the amount of virus present in the air may be cut in half in less than 10 minutes. For rooms with inadequate ventilation, this time could be more than an hour.”

To clean the air, it is key to use a proven technology like HEPA (“High Efficiency Particulate Air”) filters. Some schools are using pseudoscientific “ionizers” that may sound cool but are, at best, ineffective and at worst, actively harmful. The Hawaiʻi Department of Education published a memo in September 2021 warning schools not to use unproven ionizers, and just use tried-and-true HEPA filters instead.

Vaccination remains fundamental

With the approval of the first COVID-19 vaccine for children ages 5-11, vaccination can now play a key role in mitigating risk for younger kids — both in the classroom and in the greater community. The DOH cluster report affirmed that its number one risk mitigation strategy, shared with the DOE, is still “vaccination of eligible students and staff.” Of course, not all children will be vaccinated immediately, so other mitigation strategies — like improved ventilation and/or air filtration — are also essential.

Yes, this is a workplace risk as well

In September, I wrote about the disproportionate risk of COVID-19 exposure that Hawaiʻi’s essential workers face in the workplace. But the risk of transmission via shared air in poorly ventilated indoor spaces is present for office workers and other professions, too.

In September, the New York Times published an article, “6 Questions to Ask About Covid and Air Quality at Work,” which suggested that “[a]sking about efforts to improve indoor air quality can help you make decisions about how much time you might spend there, whether to mask up or buy a portable air cleaner or whether to change your work schedule or work from home, if it’s an option.” Those six questions, which largely mirror the factors identified in the classroom simulation, are:

- What improvements have you made to the ventilation system?

- Can the windows be opened?

- What is the air change rate?

- Are you using portable air cleaners?

- Who is monitoring air quality?

- Does the building rely on unproven technologies?

Some may note that there’s no suggested question about plastic barriers. This is because those plastic barriers can actually “change air flow in a room, disrupt normal ventilation and create ‘dead zones,’ where viral aerosol particles can build up and become highly concentrated,” according to recent research.

If this seems like a workplace safety issue, scientists are increasingly agreeing. “Ventilation is really built into the approach that OSHA takes to all airborne hazards,” Peg Seminario, who “served as director of occupational safety and health for the A.F.L.-C.I.O. from 1990 until her retirement in 2019,” told the New York Times in May. “With Covid being recognized as an airborne hazard, those approaches should apply.”

This raises the question posed by a September article in The Atlantic: “We don’t drink contaminated water. Why do we tolerate breathing contaminated air?” The article notes that this goes beyond just COVID-19: “We’ve long accepted colds and flus as inevitable facts of life, but are they? Why not redesign the airflow in our buildings to prevent them, too? … SARS-CoV-2 is unlikely to be the last airborne pandemic. The same measures that protect us from common viruses might also protect us from the next unknown pathogen.”

More context on Hawaiʻi public schools

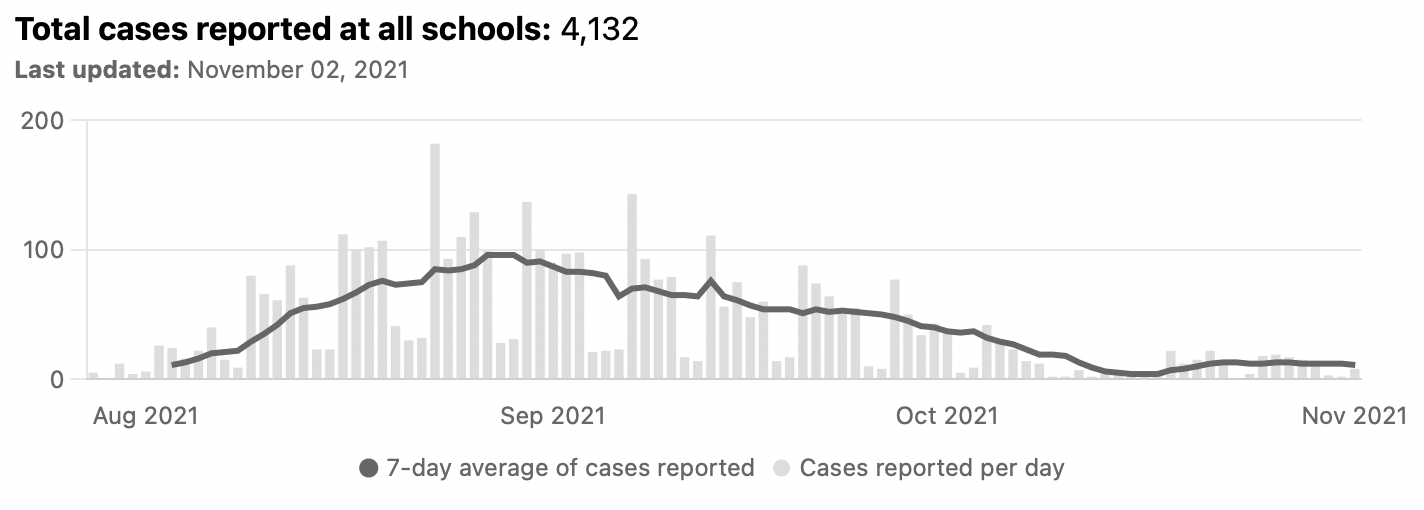

How are schools doing overall? After COVID-19 case reports peaked in late August with a daily average of 96 cases, they reached a low in mid-October, then have been steady at about a dozen daily average cases for the past week.

I continue to update my public school COVID-19 tracker daily. Unfortunately, the Department of Education’s Data Governance and Analysis Branch doesn’t provide its case data in a spreadsheet format, unlike the Department of Health, so I continue to maintain a specialized program to analyze the DOE data.