For better or worse, we live in a society where other people’s actions inevitably affect us. Although there are important actions we can take as individuals to protect our health—and the health of our community and economy—there are some things only governments can do. At a minimum, our county and state governments should at ensure residents have the tools they need to really take “personal responsibility.”

Increasing access to vaccinations, and promoting booster doses, is a good start, but it’s clear it’s not enough. So let’s steal these ideas that other cities, counties, states, and countries have already put into place:

- Educate the public about how COVID-19 spreads in shared air. Not enough people realize that enclosed, poorly ventilated spaces are inherently riskier because of COVID-19’s airborne nature. With more accurate information, people can make better decisions.

- Provide free high-filtration masks. Many may not realize that cloth masks aren’t enough to protect themselves and limit community spread. N95 masks do a far better job at protecting the wearer and reducing transmission from infected people — and they can be quite comfortable.

- Provide free rapid tests. At-home antigen tests can reliably tell people if they’re contagious at the moment they take the test. This is especially important if someone is infected but asymptomatic. However, they’re prohibitively expensive for many people.

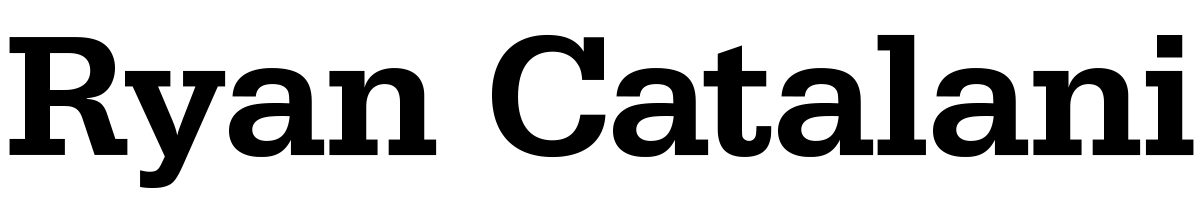

“With good ventilation, filtration, and masking, it’s easy to get a factor of 100 reduction in [COVID-19] dose,” Boston University professor and environmental health expert Jon Levy tweeted in December. “In the coming weeks, you will be in a room with someone with #COVID19. But that doesn’t mean you will get infected. The dose makes the poison, so your goal is to reduce your dose as much as possible.”

Those three ideas are discussed in greater detail below. And it’s important to note they’re not alternatives to more comprehensive public health measures. Systemic solutions would be ideal, including temporarily limiting indoor gatherings, as Hawaiʻi County has done; monitoring and improving indoor ventilation; moving high-risk, unmasked activities like dining to the outdoors; and ensuring all workers have paid sick leave, so they can afford to stay home when they or their kids are sick.

Paid leave, in particular, is something we really ought to ensure. Only 45% of Hawaiʻi’s leisure and hospitality workers have paid sick days, and service industry workers face systemic workplace risks and disproportionate exposure to COVID-19. When Governor Ige was asked back in August how working parents could keep their sick kids home without paid leave, he said he would be “sending a letter to CEOs [asking them] to be supportive,” but “it’s not a mandate.” A bill was introduced in the 2021 legislative session to ensure workers have paid sick days, but it died without a hearing.

The pandemic should have taught us by now that individual actions are not enough to fix systemic problems. “Structures inform our individual decisions every day, and…system-informed free will has real human consequences,” a February 2021 article in Slate argued, noting that “limiting one’s own public interaction is a privilege only afforded to the upper and middle classes.” This focus on individual actions creates inequities that “yield disproportionate COVID-19 disease, disability, and death in oppressed and excluded communities,” a recent paper noted, and comes at the cost of “the kind of collective actions we need to actually defeat an infectious disease,” Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ed Yong recently observed.

But at a minimum, since “personal responsibility” is now the primary policy for most of Hawaiʻi’s population, then residents need to understand how the virus is actually transmitted, be able to properly protect themselves in high-risk indoor environments, and have access to rapid tests with actionable results.

It’s like when you get into a car: Making good decisions is necessary, but not sufficient, to drive safely. We also ensure safety through government-mandated protections like seatbelts, airbags, and stoplights, and we drive confidently with a collective understanding that government requires—not merely encourages—everyone else to follow the same rules of the road. In other words, the government creates the conditions that allow individuals to take “personal responsibility.” We should do the same with the pandemic.

1. Educate the public about how COVID-19 spreads in shared air

By now, there is a firm scientific consensus that the virus spreads in shared air, even across distances greater than six feet. This means COVID-19 is spread more easily in certain settings, particularly indoors, including closed spaces with poor ventilation, crowded places, and close-contact settings—also known as the Three Cs.

But public messaging often continues to emphasize handwashing and sanitization of surfaces, which of course are important in general but not really relevant to how COVID-19 spreads. With an extremely transmissible variant like Omicron, it seems paramount that people actually understand how the virus spreads, and thus gain a better intuition about identifying risky situations.

State leaders are increasingly acknowledging the virus’s airborne nature, as I noted back in September, and encouraging people to spend time outdoors or ensure indoor spaces are well-ventilated. But this message needs greater attention and consistent reinforcement.

In November, the UK launched a media campaign, “Stop COVID-19 Hanging Around,” which demonstrates the “importance of simple ventilation techniques to reduce the risks of catching COVID-19.” Researchers there found that:

… almost two-thirds (64%) of the public did not know that ventilation was an effective way to reduce the spread of COVID-19 at home. And only around a third of people (29%) are currently ventilating their home when they have visitors over.

It’s a simple, memorable, and immediately actionable message:

Stop COVID-19 hanging around.

— NHS (@NHSuk) December 6, 2021

In enclosed spaces, COVID-19 hangs in the air like smoke. Open windows for 10 minutes each hour when socialising indoors to clear it away. pic.twitter.com/MNSFo7kERT

Other videos show a simulation of COVID-19 particles building up in an enclosed space and emphasize the importance of fresh air in restaurants.

Perhaps most notably, Japan popularized and emphasized the Three Cs model from the very beginning of the pandemic. They also created a video illustrating five situations made inherently risky by the Three Cs:

Standout media coverage on this issue includes “A room, a bar and a classroom: how the coronavirus is spread through the air” (October 2020) and “Why Opening Windows Is a Key to Reopening Schools” (February 2021).

2. Provide free high-filtration masks

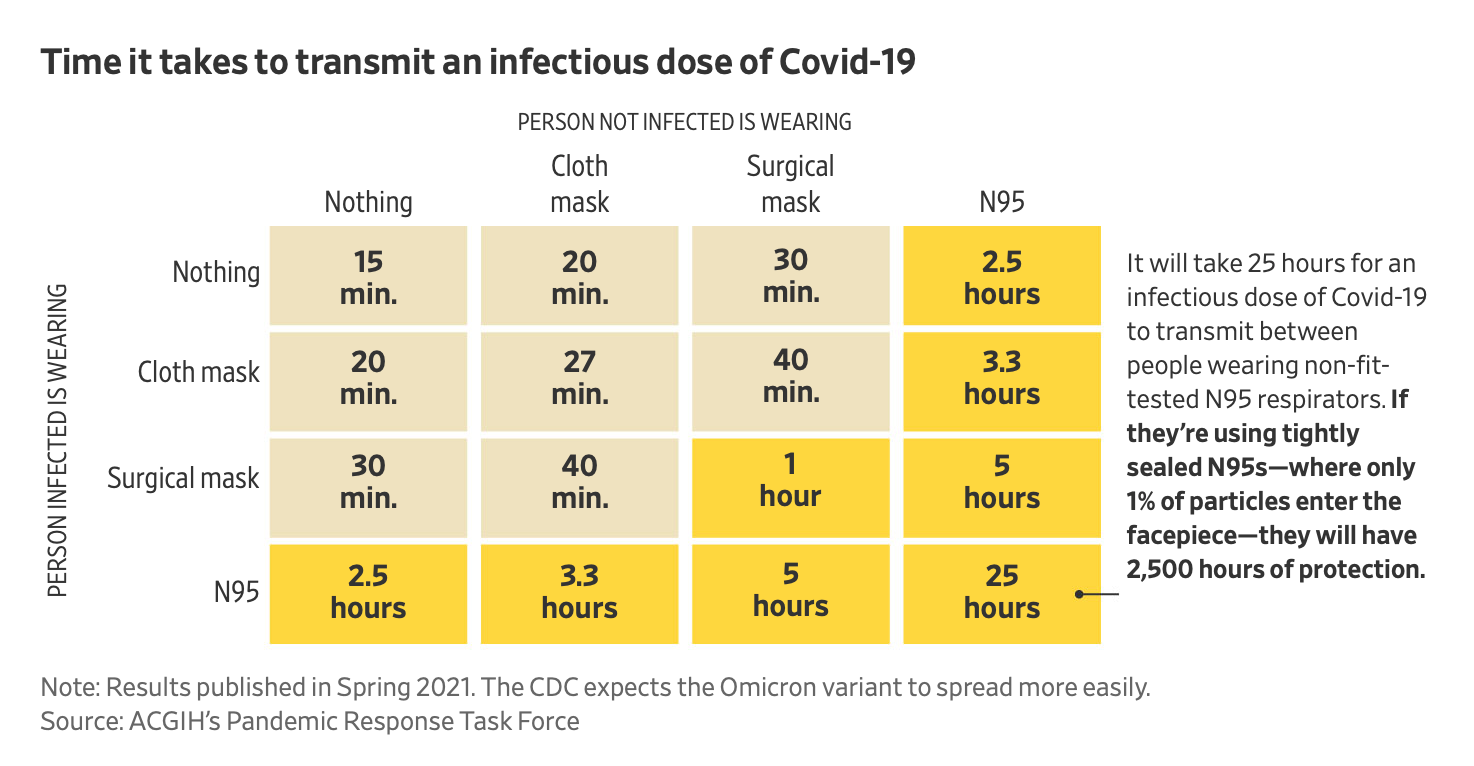

The time has come to upgrade our face masks. This is a clear recommendation from health experts. As New York Magazine wrote recently, “high filtration respirators like N95s or KN95s — which are quite comfortable, provide gold-standard protection against airborne particles, and have been widely available from reputable sellers in the U.S. for a long time — are what everyone should now be using and what every institution should be making available.”

Dr. Tim Brown from Hawaiʻi’s East-West Center echoed this message at the end of December and suggested that the state provide them for teachers and students. The state could go further and follow Connecticut’s lead, which recently announced plans to distribute 6 million N95 masks—enough to give each resident about two masks. It’s not just happening on the state level: In New York alone, a public school district, a county, and New York City all handed out N95 masks. Milwaukee is distributing 500,000 N95 masks, and LA County will require employers to provide high-quality masks to workers in high-risk environments.

Salt Lake County has taken an even stronger stance: It will require people to wear N95 or KN95 masks indoors in public. It’s also providing free N95 and KN95 masks at senior centers and libraries.

High-filtration masks are important because they provide a high degree of protection for the wearer. They substantially reduce “the chance of becoming infected with Covid-19 while in close contact with someone who has the disease.”

Linsey Marr, “one of the world’s leading experts on viral transmission,” told the New York Times that:

If I’m in a situation where I have to rely solely on my mask for protection — unvaccinated people may be present, it’s crowded, I don’t know anything about the ventilation — I would wear the best mask in my wardrobe, which is an N95. We need to wear the best masks possible in high-risk situations.

N95 masks are now widely available. I’ve been getting the 3M 9205+ Aura Particulate Respirator from a local distributor, Aloha Mask, which lists them at $1.75 each. I actually find this model quite comfortable—even more so than cloth masks—and others have agreed. (In fact, the FDA cleared similar models for “use by the general public in public health medical emergencies” in 2008, according to 3M, but they were “discontinued in 2013 following a long period of inactivity.”) One could imagine that the purchasing power of a county or the state could make them even more affordable to purchase and distribute on a large scale. The nonprofit Project N95 also helps local and state governments source authentic products.

High-filtration masks can even be reused “many times” until “they are dirty, damaged or difficult to breathe through,” according to 3M’s helpful guidance on respirators for the general public. The inventor of the N95 mask material suggested having three or four masks could be enough, if you use one per day and rotate them, because “SARS-CoV-2 viruses on the mask will be dead in 3 days.”

3. Provide free rapid tests

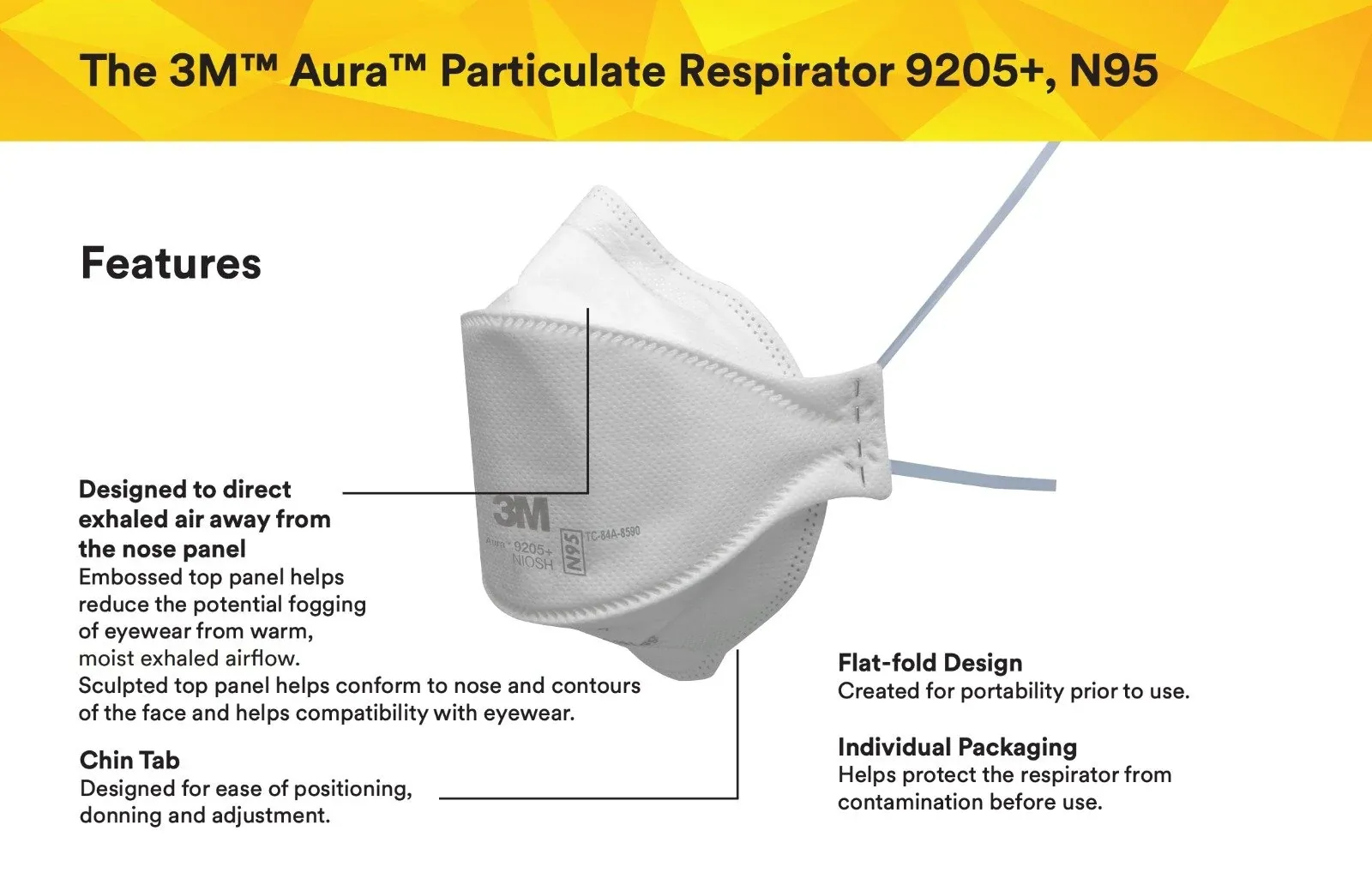

Rapid antigen tests help people answer a critical question with a high degree of accuracy: Am I infectious right now? They can be taken at home—before heading out to work, school, or a social gathering—and produce results in about 15 minutes, whether or not you have symptoms.

If everyone used rapid tests regularly, they could be a “good way to see who is infectious and who can return to public life,” as Zeynep Tufekci recently wrote. Back in February 2021, an article in Nature argued rapid tests could “help to curb the pandemic by quickly identifying the most contagious people, who might otherwise unknowingly pass on the virus.” Researchers believe a significant proportion of cases are unwittingly spread by infected people who don’t have symptoms—a problem that may be exacerbated with Omicron.

But there’s a big problem. Rapid tests are pretty expensive (about $10-12 per test) and, especially during the Omicron-driven surge, hard to find. For families who can afford these tests, the costs are quickly reaching hundreds of dollars, the New York Times recently reported.

Although President Biden pledged to make 500 million rapid tests available to the public, that quantity is only enough for an average of 1.5 tests per person. Here in Hawaiʻi, Maui County has twice distributed at least “a few thousand” tests, which is a commendable start. (Also, last fall, the state Department of Health participated in a federal pilot project that distributed free tests to 125,000 Oʻahu residents.) Governor Ige told the Star-Advertiser today that the state is trying to procure rapid tests but “can't find a vendor who wants to sell it to us.”

The current surge underscores just how valuable rapid tests could be. Hawaiʻi’s county and state governments could follow the lead of others across the country distributing free rapid tests. This is just a small sampling:

- Washington, DC: Residents can pick up two kits (four tests) per day at public libraries — there’s even a live inventory tracker

- Washington: 5.5 million rapid tests

- New York City: 500,000 tests

- Sacremento County: 91,000 tests distributed at public libraries

- Miami-Dade County Public Schools: Tests available for students and employees

- Select airports (though none in Hawaiʻi so far)

Even these laudable efforts pale in comparison to other countries. In October, CBS reported that in England, “they're readily available at pretty much every pharmacy in the country. Anyone can just walk in and ask for them – and they're completely free, usually distributed in boxes of five or seven. You can go back and get as many as you need.” You can even order one free pack (seven tests) per day right from the government. In Singapore, the government “began mailing out six rapid test kits to every household in September” and in Canada, “businesses can request free rapid test kits for their staff,” according to The Independent.

My brother’s mail this morning, living in the UK outside of London. Free from the government. State capacity is a thing. pic.twitter.com/h4rYM9aGlW

— Noah Rosenblum (@narosenblum) December 29, 2021

The free mass PCR testing sites organized by the state, city, and private partners continue to provide an important diagnostic service. And rapid tests aren’t perfect. A negative test “should not be used as a ‘green light’ to act as if you definitely don’t have Covid,” nor “stop exercising caution in crowded spaces,” a British expert recently wrote in the New York Times. “It can make activities much safer, but not completely ‘safe’ from infection risk.” But he continued:

… when these tests are cheap and easy to get and use, they can greatly help aid or even replace reliance on expensive and often time-consuming PCR test screening programs in communities, especially in places like schools. If rapid tests are used immediately before an event, like a holiday gathering, they can lower risk of infections and make gatherings safer. Using rapid tests regularly should become a social norm. … If you want to maximize the benefits of rapid testing, take your test immediately before going out, not the day before.