Beyond the expected exhortation to stay at home, Governor David Ige’s public statement on September 2 contained an auspicious shift in the state’s public messaging about the pandemic: a renewed emphasis on the danger of poorly ventilated spaces in the transmission of COVID-19.

Though messaging alone certainly can’t end the pandemic, this change has the power to bolster public understanding of basic pandemic dynamics — which still appears to be a source of confusion for many — and thus help people reduce risk.

Starting around August 2020, until this latest statement, the state had hewed to a mnemonic popularized by the former US Surgeon General Jerome Adams, the “Three Ws”: “wash your hands, watch your distance, and wear your mask when out and about.” After Dr. Adams’ visit to Hawaiʻi in August 2020, Governor Ige had repeated those three Ws at almost every press conference about the pandemic, framing them as the key prevention strategies to stay safe (in addition to testing and, more recently, vaccination).

There can be no doubt that those three recommendations are helpful and important to do. Governor Ige should also be commended for holding firm on requiring masks indoors, even when, at one point, Hawaiʻi was the only state to continue this mandate. But by centering “washing your hands,” this catchphrase counterproductively overemphasized the risk of COVID-19 transmission via contact with surfaces, which is actually rare. It also omits the critical fact that COVID-19 can spread over longer distances, particularly in enclosed, poorly ventilated spaces. (Though it took a while, the CDC and WHO started acknowledging this mode of transmission in May 2021.)

Without understanding how COVID-19 spreads, the public can’t make good decisions

This basic matter of how COVID-19 spreads seems to be a continuing source of confusion. Within the past month, I heard someone wondering about the risk of getting sick from touching a grocery store shopping cart. I heard someone else loudly exclaim that COVID-19 “is not airborne.” These interactions seem indicative of the general public’s understanding: that COVID-19 only spreads via surfaces (which is quite uncommon) and short-range, unmasked contact (which is an incomplete picture). Scientists may still quibble over the technical definition of “airborne,” but there’s no doubt at this point among experts that people can get sick from virus-filled particles exhaled by others at a distance greater than 3-6 feet away.

City and state leaders have occasionally discussed the risk of enclosed spaces — and the importance of ventilation — but with one laudable exception in July 2020, it’s never been a cornerstone of public messaging. (This is true of federal leaders too.) Businesses and other public facilities have myriad signs about masks and physical distancing — and even highlight less effective measures like temperature checks and “deep cleaning” — but it’s rare to see an emphasis on air filtration and ventilation, with some rare but praiseworthy outliers.

At the state government level, perhaps the most frequent discussion has been in the Department of Health’s cluster reports, including the most recent one on September 2. (Thank you to the author(s) of those reports for consistently trying to raise this point.) DOH officials have also mentioned it in a few press releases and in a CDC-published paper about transmission in gyms. In the Department of Education’s 2021-22 guidance for schools, increasing ventilation is described as an “additional mitigation strategy,” not a “core essential strategy.” The City and County of Honolulu includes it in its requirements for events and its (non-binding) advice for businesses. The CDC published advice for ventilation in homes and businesses as part of a “layered approach.” These references, though, tend to be more peripheral rather than a core component, though this is slowly changing.

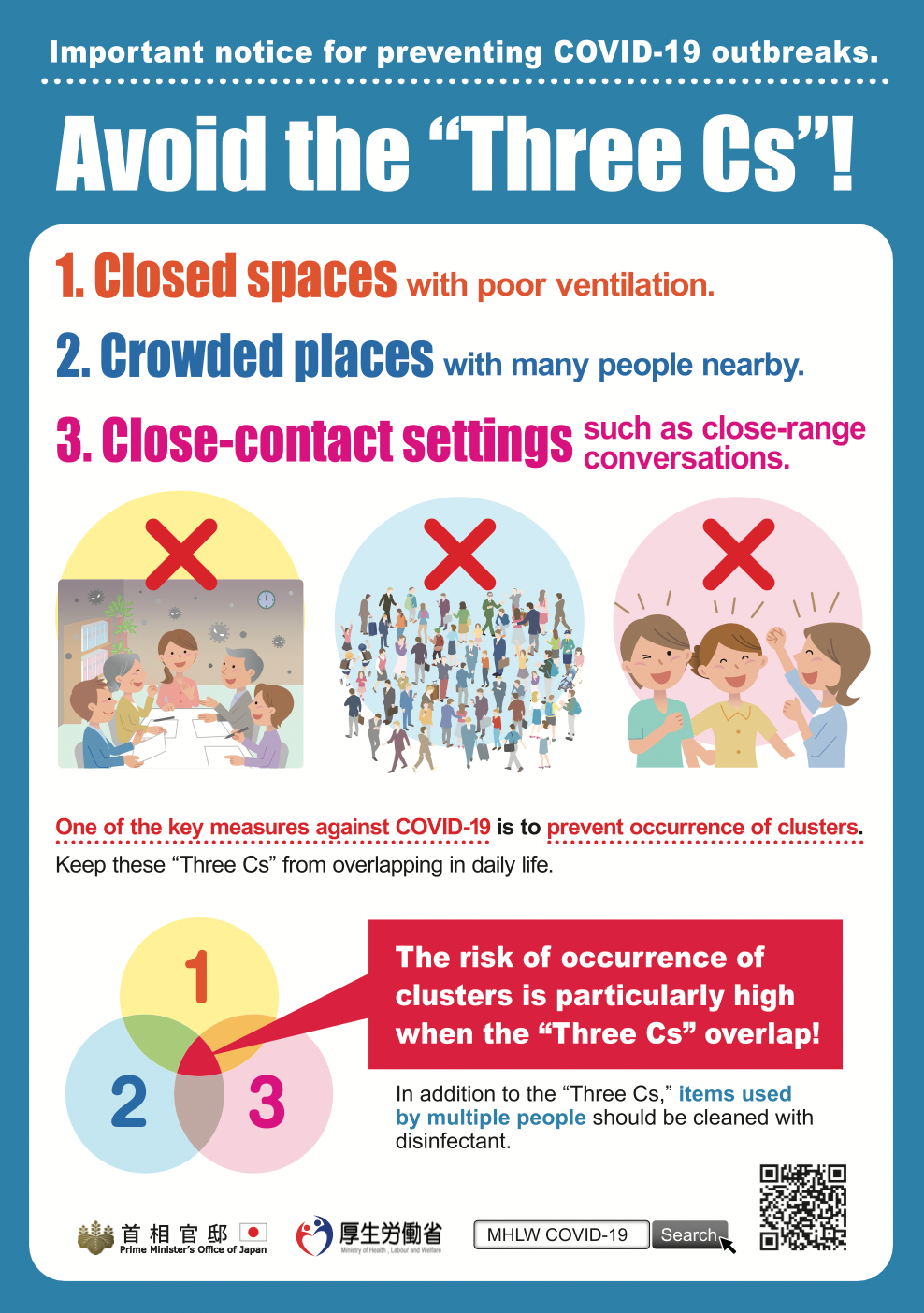

From early on, Japan’s 3Cs model clearly and pragmatically explained how COVID-19 spread

Japanese officials recognized the COVID-19 transmission dynamics almost immediately. By March 2020, they had created an alternate mnemonic, the “Three Cs”: avoid “closed spaces with poor ventilation,” “crowded places with many people nearby,” and “close-contact settings such as close-range conversations.” In an English-language handout from April 2020, the Japanese prime minister’s office’s top recommendation was to increase ventilation: “You cannot assume large rooms to be safe or small rooms to be dangerous. The key is the degree of ventilation.” (The Japanese materials also mentioned hand washing and sanitization as practices that should generally occur anyway, not specifically as a key measure to stop the spread of COVID-19.)

One recent paper called Japan’s Three Cs campaign a “notable example of clear and effective public health messaging.” This strategy came from an early realization that “most clusters originated in gyms, pubs, live music venues, karaoke rooms, and similar establishments where people gather, eat and drink, chat, sing, and work out or dance, rubbing shoulders for relatively extended periods of time,” according to the journal Science. (Indeed, it is exactly those conditions that the latest Hawaiʻi DOH cluster report focuses on.) Japanese officials “also concluded that most of the primary cases that touched off large clusters were either asymptomatic or had very mild symptoms.”

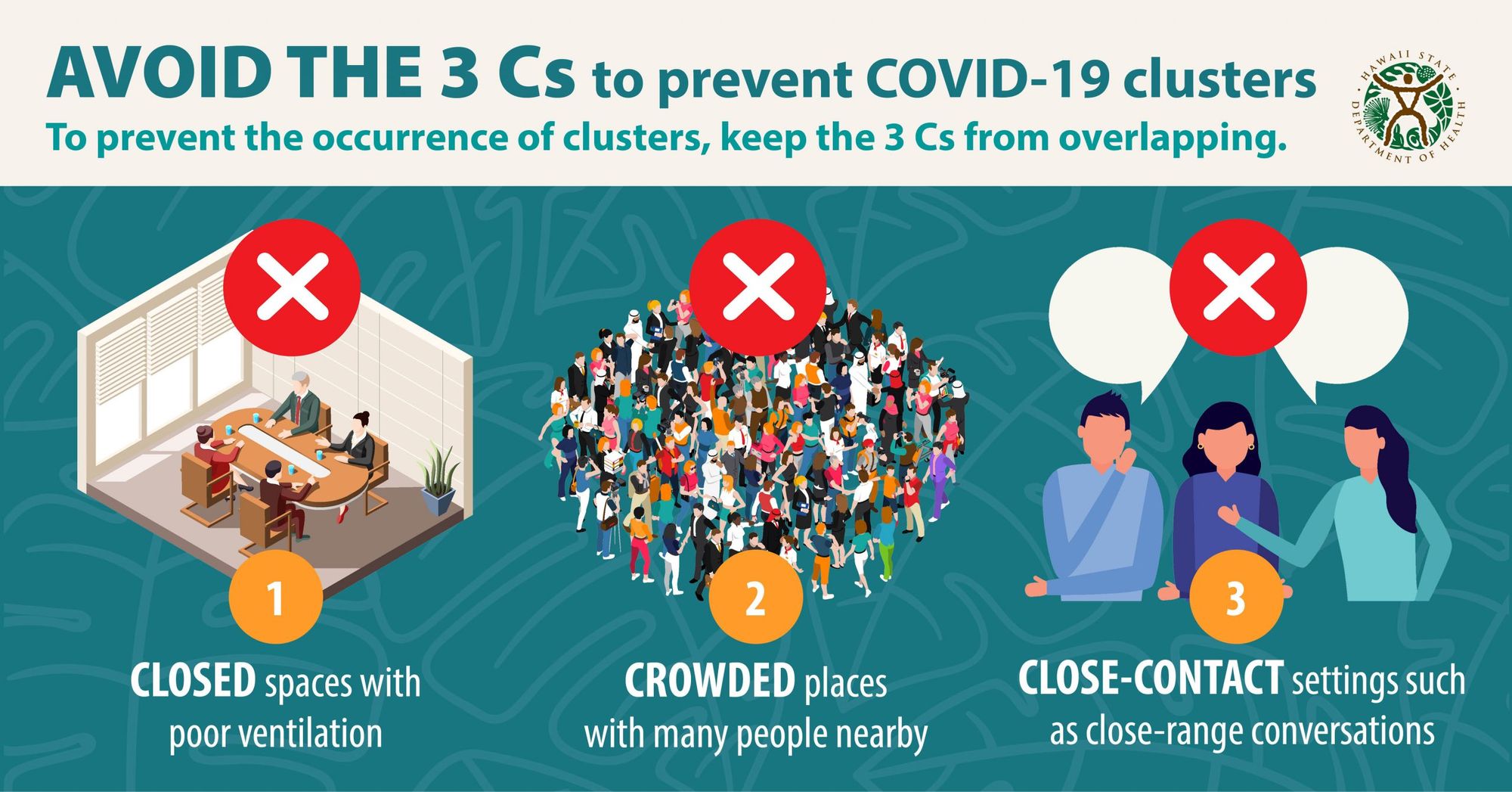

In a fairly significant shift, Governor Ige’s latest statement ahead of Labor Day used Japan’s Three Cs model, albeit without naming it specifically. (He did also include the Three Ws, but this time, it was a secondary part, outside of the main focus.)

There’s no documented instance of Governor Ige personally using the Three Cs model before last week. Former DOH director Bruce Anderson mentioned it in a June 2020 press release, and the DOH even created a graphic and social media posts using the Three Cs in July 2020, ahead of the Independence Day holiday.

Others in Hawaiʻi have sometimes referenced the model since then, but the campaign last July was the last major public use until this month. After Governor Ige’s statement, Kauaʻi Mayor Derek Kawakami echoed the Three Cs mnemonic on September 3.

Back in March 2020, Japan also produced a clear, concise English-language PSA that explains the Three Cs and describes five particularly risky social situations, given the way COVID-19 is transmitted:

- Social gatherings with drinking. (“People tend to get excited and speak loudly,” the video points out.)

- Long meals in large groups. (Of course, you can’t wear a mask while eating.)

- Conversation without wearing a mask.

- Living together in small, limited spaces.

- Switching locations. (“During times like work breaks, we tend to forget about preventing transmission,” the video specifies.)

It’s hard not to wonder how different things might look in this country if we had a higher degree of clarity about COVID-19 transmission. How might behaviors and policies have changed if the general public realized that certain settings — enclosed places with poor ventilation, where people interact in close contact without wearing masks — are inherently riskier? What would it mean for schools? Might we have found alternate ways to support both public health and economic health — for example, by assiduously promoting open-air dining like other cities? (Honolulu’s forthcoming “Safe Access” program, which requires proof of vaccination or testing at high-risk venues like restaurants, bars, and gyms, is another evidence-based step in the right direction.)

Governor Ige’s latest statement is a welcome change (or perhaps reversion) to a messaging model that better educates the public on how COVID-19 spreads. It’s a necessary complement to continued efforts around vaccination, testing, masking, and physical distancing. Will we see this message repeated enough to improve public understanding? Does the new messaging signal a parallel shift in public policy? With the latest surge still unabated, anything more we can do to stop the spread is critical.

Further reading

One of the most effective illustrations of the dangers of enclosed spaces is this October 2020 article, “A room, a bar and a classroom: How the coronavirus is spread through the air,” published in Spain’s El País newspaper (in English).

That article is based on research by José Luis Jiménez, Ph.D., who, with a group of other scientists and engineers, wrote these “FAQs on Protecting Yourself from COVID-19 Aerosol Transmission.” In addition to the Three Cs, these scientists also emphasize the risk of “talking / singing / shouting / breathing hard,” which are activities that increase the risk of exhaling infectious particles.

In March 2021, the journal Nature published a story about “Why indoor spaces are still prime COVID hotspots”: “Many experts say that enough is known for authorities to provide a clear message about how important good ventilation is for safety indoors, especially in spaces that are continuously occupied, or where masks are removed when eating.”

What’s a good, practical way to remember this? One that has stuck with me is from Abdul El-Sayed, MD, Ph.D., who suggested this metaphor: “Imagine you are constantly blowing little bubbles from your mouth. Where will those bubbles go? If you were outdoors, they’d be blown away pretty quickly. And if they’re indoors, they stay, just sitting there waiting for them to hit somebody else’s nose or mouth. And that’s exactly what we’re doing all the time, we just can’t see the bubbles. And so outdoors is better than indoors.”